Earlier this week I shared a tutorial on using OpenCV to stream live video over a network via ImageZMQ — and today I’m pleased to share an interview with Jeff Bass, the creator of ImageZMQ!

Jeff has over 40 years experience hacking with computers and electronics — and now he’s applying computer vision + Raspberry Pis to his permaculture farm for:

- Data collection

- Wildlife monitoring

- Water meter and temperature reading

Jeff is truly one of my favorite people that I’ve ever had the honor to meet. Over his 40 year career he’s amassed an incredible amount of knowledge over computer science, electronics, statistics, and more.

He also spent 20 years doing statistics and data analysis at a large biotech company. The advice he gives is practical, to the point, and always very well said. It’s a privilege to have him here today.

On a personal note, Jeff was also one of the original PyImageSearch Gurus course members. He’s been a long-time reader and supporter — and he’s truly helped make this blog possible.

It’s a wonderful pleasure to have Jeff here today, and whether you’re looking for unique, practical applications of computer vision and OpenCV, or simply looking for advice on how to build your portfolio for a career in computer science, look no further than this interview!

An interview with Jeff Bass, creator of ImageZMQ

Adrian: Hey Jeff! Thank you for being here today. It’s wonderful to have you here on the PyImageSearch blog. For people who do not know you, who are you and what do you do?

Jeff: I’m a lifelong learner who’s been playing with electronics and computers for over 40 years. I studied econometrics, statistics and computer science in grad school. I developed a statistical software package for PCs back when PCs were a new thing. I spent 20 years doing statistics and data analysis at a big biotech company.

Now I’m retired from income producing endeavors and building a small permaculture farm in Southern California. I’m using computer vision, sensors and Raspberry Pis as tools to observe and manage the farm. I speak at garden clubs and conferences occasionally. I really enjoyed being a speaker at PyImageConf 2018.

Adrian: How did you first become interested in computer vision and deep learning?

Jeff: I got a Raspberry Pi and a Pi Camera module in 2013 when they first became available. I wanted to use them to observe and catalog wildlife activity as I got started with the farm. I was already very familiar with Linux and C, but the best Pi Camera interface was the “Picamera” module in Python. I started “web wandering” to learn more about Python programming and computer vision. I ran across your tutorial blogs and bought your Practical Python and OpenCV book. Once I’d worked through the examples in your book, I was hooked.

Adrian: Can you tell us a bit more about your farm? What is permaculture farming? Why is it important and how is it different than “traditional” farming?

Jeff: I call the farm Yin Yang Ranch. It is a small 2 acre “science project” in a suburban area. I started learning about permaculture at the same time I started learning about Raspberry Pis.

Permaculture is a collection of practices and design principles to grow food with long term sustainability as the primary goal. It starts with creating deep living soil with diverse microbiology, emulating an old growth forest. Permaculture design choices prioritize sustainability over efficiency. It is science based, emphasizing a cycle of careful observation, repeatable experiments and open sharing of best practices.

Permaculture farms are generally small and include many different kinds of plants growing together rather than rows of similar crops. Food plants are grown in the same space with native plants. I am growing figs, pears, pomegranates, plums, grapes, avocados, oranges, mulberries, blackberries and other edibles. But they are interplanted with native California Coast Live Oaks and Sycamore Trees. It doesn’t look much like a traditional farm. Traditional agriculture is efficient, but degrades soil and water resources. Permaculture is trying to change that.

Adrian: How can Raspberry Pis and computer vision be helpful on your farm?

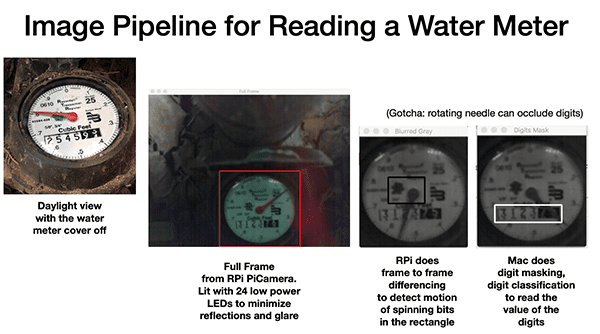

Jeff: We are in Southern California about 10 miles from the Malibu coast. Drought and limited rainfall are the toughest climate issues. Monitoring and observation are important, so I built a Raspberry Pi Camera system to read the water meter and monitor temperatures to optimize irrigation.

That led more questions and lots of fun ways to gather and analyze data:

- How many gallons did it take to water the mulberries today?

- When did the coyotes last run behind the barn?

- What is the temperature and soil moisture under the avocado trees?

- What is the temperature and moisture content of the 5 compost piles?

- How is it changing over time?

- How much solar electricity did we generate today?

- How full are the rain barrels?

- How do the birds, butterflies and other critter movements change with the seasons and with whatever is blooming or putting on fruit?

The Raspberry Pis are also keeping track of stuff like the opening and closing of garage and barn doors. And they can let me know when a package is delivered.

Adrian: You created a library called imagezmq. What is it and what does it do?

Jeff: The imagezmq library implements a simple and fast network of Raspberry Pis (clients) and servers.

Early on, I decided on a distributed design using Raspberry Pis for capturing images and using Macs for analyzing the images. The goal was to have Raspberry Pis do image capture and motion detection (is the water meter spinning?) and programmatically decide on a small subset of images to pass along to the Mac.

I spent a year trying different ways of sending images from multiple Raspberry Pis to a Mac. I settled on the open source ZMQ library and its PyZMQ python wrappers. My imagezmq library uses ZMQ to send images and event messages from a dozen Raspberry Pis to a Mac hub. ZMQ is fast, small, simple to use and doesn’t need a message broker.

Here are a pair of code snippets showing how to use imagezmq to continuously send images from a Raspberry Pi to a Mac. First the code running on each Raspberry Pi:

# run this program on each RPi to send a labelled image stream import socket import time from imutils.video import VideoStream import imagezmq sender = imagezmq.ImageSender(connect_to='tcp://jeff-macbook:5555') rpi_name = socket.gethostname() # send RPi hostname with each image picam = VideoStream(usePiCamera=True).start() time.sleep(2.0) # allow camera sensor to warm up while True: # send images as stream until Ctrl-C image = picam.read() sender.send_image(rpi_name, image)

Then the code running on the Mac (server):

# run this program on the Mac to display image streams from multiple RPis import cv2 import imagezmq image_hub = imagezmq.ImageHub() while True: # show streamed images until Ctrl-C rpi_name, image = image_hub.recv_image() cv2.imshow(rpi_name, image) # 1 window for each RPi cv2.waitKey(1) image_hub.send_reply(b'OK')

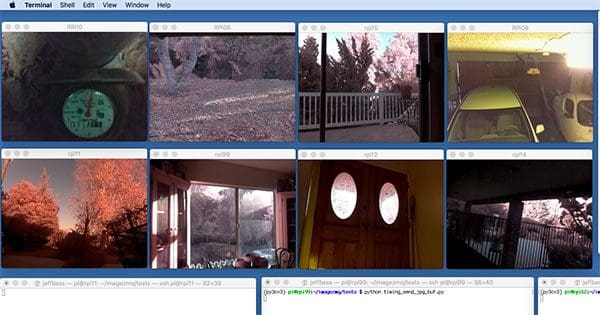

The hostname of each Raspberry Pi allows the Mac to put the image stream from that Raspberry Pi in a separate, labelled cv2.imshow() window. I have a photo in my imagezmq github repository showing 8 Raspberry Pi camera feeds being displayed simultaneously on a single Mac:

It uses 12 lines of Python code on each Raspberry Pi and 8 lines of Python on the Mac. One Mac can keep up with 8 to 10 Raspberry Pis at 10 FPS. ZMQ is fast.

imagezmq enables a computer vision pipeline to be easily distributed over multiple Raspberry Pis and Macs. The Raspberry Pi captures images at 16 FPS. It detects motion caused by the spinning of the water meter needle. It sends only the images where the needle starts moving or stops moving, which is only a small fraction of the images it captures. Then, the Mac uses more advanced computer vision techniques to read the “digital digits” portion of the water meter images and determine how much water is being used. Each computer is able to do the portion of the computer vision pipeline for which it is best suited. imagezmq enables that.

Adrian: What is your favorite computer vision + Raspberry Pi project that you’ve deployed on Yin Yang Ranch?

Jeff: I’ve mounted a Raspberry Pi on the back wall of my barn with an infrared floodlight. It tracks motion and sends images when the motion is “critter like”. I’ve captured images of coyotes, raccoons, possums, bats, hawks, squirrels and rabbits. I’m still working on the deep learning models to classify them correctly. It’s been a lot of fun for me and my neighbors to learn more about the wildlife around us.

Adrian: Raspberry Pis, while cheap, are by no means as powerful as a standard laptop/desktop. What are some of the lessons learned while using Raspberry Pis around the farm?

Jeff: Raspberry Pis are great at image capture. The Pi Camera module is very controllable in Python for changing things like exposure mode. A USB or laptop webcam is usually not controllable at all. Controlling exposure and other camera settings can be very helpful in wildlife tracking and even reading a water meter.

The Raspberry Pi GPIO pins can gather readings from temperature sensors, moisture sensors and others. The GPIO pins can be used to control lights like the lights that illuminate my water meter and my barn area. Laptops and desktops don’t do those things easily.

On the other hand, Raspberry Pis lack a high speed disk drive — the SD card is not suitable for writing lots of binary image files. In my system, the Raspberry Pis send the image files over the network rather than storing them locally. Laptops and desktops have fast disk storage and lots of RAM memory allowing more elaborate image processing. I try to have my Raspberry Pis do what they excel at and have the Macs do what they are good at.

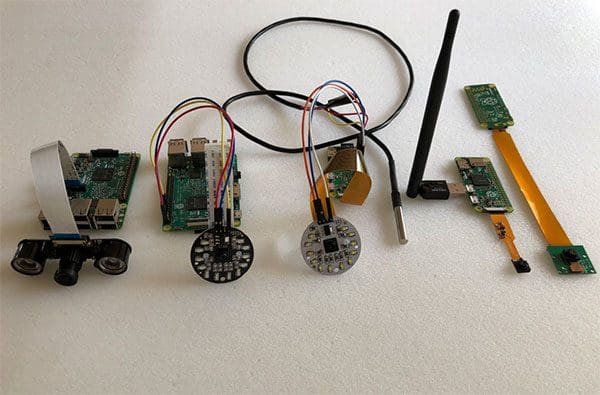

Most of my Raspberry Pis are Raspberry Pi 3’s, but I also use the cheaper, smaller Raspberry Pi Zero for Pi Cameras that only need to do simple motion detection, like my driveway cam. When there is no need for additional image processing, even the smaller memory and less powerful processor of the Pi Zero is adequate.

Adrian: What types of hardware, cameras, and Raspberry Pi accessories do you use around the farm? How do you keep your Pis safe from getting wet and destroyed?

Jeff: I use Raspberry Pis with Pi Cameras at many places around the farm. They often have temperature, moisture and other sensors. I build multiple kinds of enclosures to protect the Raspberry Pis.

One of my favorites is to convert a existing outdoor light fixture into a waterproof Raspberry Pi container. You remove the light bulb, screw in a simple AC socket adapter and you have an easy rainproof enclosure that holds the Raspberry Pi and the Pi Camera module. A GPIO temperature probe fits as well. It is easy to add a Raspberry Pi controlled LED light so that the light fixture still provides light like it did before:

Another enclosure is a simple glass mason jar with a plastic lid. It fits a Raspberry Pi and is waterproof. Power and camera cables can be routed through holes in the plastic lid. That’s how my water meter Pi Camera is built and it has been working well through all kinds of weather for over 2 years:

For infrared applications like the night time critter camera behind my barn, I put the Raspberry Pi inside the barn. The camera and temperature sensor cables run through small holes in the barn wall. The Pi NoIR camera module is protected under a simple overhang of old shingles. Infrared light doesn’t pass through glass, so the Pi NoIR camera module cannot be in a glass enclosure. The shingle overhang over an otherwise unprotected PiNoIR module has been very effective:

A closer view can be seen below:

I have also found that inexpensive (about $5) “Fake Security Cam” enclosures work really well as waterproof Raspberry Pi and Pi Camera enclosures. They easily hold a Raspberry Pi and they have a tripod-like angle adjuster:

Once put together the “fake” security camera becomes a real security camera:

For power, I tend to run longer power lines (over 20 feet long) at 12 volts, then convert to 5 volts at the Raspberry Pi. I use 12 volt power adapters like those that are used to charge cell phones in cars. Cheap and effective. Most of my Raspberry Pis are networked with WiFi, but I have ethernet in my barn and at various places around the house, so some of my Raspberry Pis are using ethernet to send images.

Adrian: During your PyImageConf 2018 talk you discussed how projects like these can actually help people build their computer vision and deep learning resumes. Can you elaborate on what you mean there?

Jeff: During my 30 years of managing programming and data analysis teams, I found it very helpful when job candidates came to the interview with a specific project in their portfolio that showed their strengths. A computer vision project — even a hobby project like my Raspberry Pi water meter cam — can really help demonstrate practical skills and ability.

A well documented project demonstrates practical experience and problem solving. It shows the ability to complete large projects fully (80% solutions are good but 100% solutions demonstrate an ability to finish). A portfolio project can demonstrate other specific skills, such as using multiple computer vision libraries, the ability to write effective documentation, facility with Git / GitHub as a collaboration tool and technical communication skills. It is important to be able to tell a short, compelling project story — the “elevator speech” about your portfolio project.

Adrian: How as the PyImageSearch blog, the PyImageSearch Gurus course, and the books/courses helped you make this project a success?

Jeff: When I started learning about computer vision, I found that a lot of the material on the web was either too theoretical or gave simplistic code snippets without any fleshed out examples or complete code.

When I found your PyImageSearch blog, I found your tutorial projects to be very complete and helpful. You provided an understandable story line for each problem being solved. Your explanations were clear and complete with fully functioning code. Running some of the programs in your blog led me to buy your Practical Python and OpenCV book.

I took your PyImageSearch Gurus course and learned to code many specific computer vision techniques. I had previously read about many of these techniques, but your specific code examples provided the “how-to” I needed to write computer vision code for my own projects.

The license plate number reading section of your Gurus course was the basis for the first draft of my water meter digits reading program. Your deep learning book is helping me to write the next version of my object recognition software for tagging critters around the farm (racoon or possum?).

Adrian: Would you recommend PyImageSearch and the books/courses to other developers, researchers, and students trying to learn computer vision + deep learning?

Jeff: I would definitely recommend your PyImageSearch blog, books and courses to those trying to learn about this rapidly evolving field. You are very good at explaining complex techniques with a helpful mix of code and narrative discussion. Your books and courses provided a jump start to my understanding of the theory and practice of modern computer vision algorithms.

I had not programmed in Python before, and some of its idioms felt a bit odd to my C conditioned brain. Your practical examples helped me use the best features of Python in “Pythonic” ways. Your Gurus course is well structured with a good flow that builds on simple examples that are expanded lesson by lesson into fully developed programs that solve complex problems. Your coverage of the many different computer vision and deep learning techniques is broad and comprehensive. Your books and courses are a good value for what you charge for them. Highly recommended.

Adrian: What are your next steps for Yin Yang Ranch and your current computer vision/deep learning projects?

Jeff: I would like to do more wildlife identification and counting. The farm is next to an open space that is a wildlife corridor through a suburban area. I’m going to use more advanced deep learning techniques to identify different animals by species. When do specific animals come and go? What birds and butterflies show up in which part of the season? How are their numbers related to seasonal rainfall? I would like to use deep learning to identify specific individuals in a coyote pack. How long is a specific coyote staying in our area? I can recognize specific individuals when I look at captured images. I’d like to use deep learning to do that with software.

Adrian: Is there anything else you would like to share?

Jeff: Building stuff with software and hardware can be a lot of fun. If someone is reading this and wondering how to get started, I would suggest they start with something they are passionate about. There is likely to be some way that computer vision and deep learning can help with a project in their area of interest. I wanted to do some permaculture farm science and my computer vision projects are helping me do that. I’m learning a lot, giving some talks and farm tours to help others learn…and I’m having a lot of fun.

Adrian: If a PyImageSearch reader wants to chat, what is the best place to connect with you?

Jeff: Folks can read more and see more project pictures at my Yin Yang Ranch repository on GitHub:

https://github.com/jeffbass/yin-yang-ranch

Or they can send me an email at jeff [at] yin-yang-ranch.com.

What's next? We recommend PyImageSearch University.

86+ total classes • 115+ hours hours of on-demand code walkthrough videos • Last updated: July 2025

★★★★★ 4.84 (128 Ratings) • 16,000+ Students Enrolled

I strongly believe that if you had the right teacher you could master computer vision and deep learning.

Do you think learning computer vision and deep learning has to be time-consuming, overwhelming, and complicated? Or has to involve complex mathematics and equations? Or requires a degree in computer science?

That’s not the case.

All you need to master computer vision and deep learning is for someone to explain things to you in simple, intuitive terms. And that’s exactly what I do. My mission is to change education and how complex Artificial Intelligence topics are taught.

If you're serious about learning computer vision, your next stop should be PyImageSearch University, the most comprehensive computer vision, deep learning, and OpenCV course online today. Here you’ll learn how to successfully and confidently apply computer vision to your work, research, and projects. Join me in computer vision mastery.

Inside PyImageSearch University you'll find:

- ✓ 86+ courses on essential computer vision, deep learning, and OpenCV topics

- ✓ 86 Certificates of Completion

- ✓ 115+ hours hours of on-demand video

- ✓ Brand new courses released regularly, ensuring you can keep up with state-of-the-art techniques

- ✓ Pre-configured Jupyter Notebooks in Google Colab

- ✓ Run all code examples in your web browser — works on Windows, macOS, and Linux (no dev environment configuration required!)

- ✓ Access to centralized code repos for all 540+ tutorials on PyImageSearch

- ✓ Easy one-click downloads for code, datasets, pre-trained models, etc.

- ✓ Access on mobile, laptop, desktop, etc.

Summary

In this blog post, we interviewed Jeff Bass, the creator of the ImageZMQ library (which we used in last weeks’s tutorial), used to facilitate live video streaming from a Raspberry Pi to a central server/hub using Python + OpenCV.

Jeff was motivated to create the ImageZMQ library to help around his permaculture farm. Using ImageZMQ and a set of Raspberry Pis, Jeff can apply computer vision and data science techniques to gather and analyze temperature readings, water meter flow, electricity usage, and more!

Please take a second to thank Jeff for taking the time to do the interview.

To be notified when future blog posts and interviews are published here on PyImageSearch, just be sure to enter your email address in the form below, and I’ll be sure to keep you in the loop.

Join the PyImageSearch Newsletter and Grab My FREE 17-page Resource Guide PDF

Enter your email address below to join the PyImageSearch Newsletter and download my FREE 17-page Resource Guide PDF on Computer Vision, OpenCV, and Deep Learning.